New Stock Market Crash Inevitable

Every production phase or society or other human invention goes through a so-called transformation process. Transitions are social transformation processes that cover at least one generation. In this article I will use one such transition to demonstrate the position of our present civilization and that a new stock market crash is inevitable.

When we consider the characteristics of the phases of a social transformation we may find ourselves at the end of what might be called the third industrial revolution. Transitions are social transformation processes that cover at least one generation (= 25 years). A transition has the following characteristics:

- it involves a structural change of civilization or a complex subsystem of our civilization

- it shows technological, economical, ecological, socio cultural and institutional changes at different levels that influence and enhance each other

- it is the result of slow changes (changes in supplies) and fast dynamics (flows)

A transition process is not fixed from the start because during the transition processes will adapt to the new situation. A transition is not dogmatic.

Four transition phases

When we consider the characteristics of the phases of a social transformation we may find ourselves at the end of what might be called the third industrial revolution.

Figure: Four phases in a transition best visualized by means of an S – curve: Pre-development, Take off, Acceleration, Stabilization.

The S curve of a transition

In general, transitions can be seen to go through the S curve and we can distinguish four phases (see fig. 1):

- a pre-development phase of a dynamic balance in which the status does not visibly change

- a take-off phase in which the process of change starts because of changes in the system

- an acceleration phase in which visible structural changes take place through an accumulation of socio cultural, economical, ecological and institutional changes influencing each other; in this phase we see collective learning processes, diffusion and processes of embedding

- a stabilization phase in which the speed of sociological change slows down and a new dynamic balance is achieved through learning

A product life cycle also goes through an S curve. In that case there is a fifth phase:

- the degeneration phase in which cost rises because of over capacity and the producer will finally withdraw from the stock market .

When we look back into the past we see three transitions, also called industrial revolutions, taking place with far-reaching effect:

- The first industrial revolution (1780 until circa 1850); the steam engine

- The second industrial revolution (1870 until circa 1930); electricity, oil and the car

- The third industrial revolution (1950 until ....); computer and microprocessor

The emergence of a stock market boom

In the development and take-off phases of the industrial revolution many new companies emerged. All these companies went through more or less the same cycle simulataneously. During the second industrial revolution these new companies emerged in the steel, oil, automotive and electrical industries, and during the third industrial revolution the new companies emerged in the hardware, software, consulting and communications industries. During the acceleration phase of a new industrial revolution many of these businesses tend to be in the acceleration phase of their life cycle, more or less in parallel.

Figure: Typical course of stock market development: Introduction, Growth, Flourishing and Decline

There is an enormous increase in expected value of the shares of companies in the acceleration phase of their existence. This is the reason why shares become very expensive in the acceleration phase of a revolution.

There was also an enormous increase in price-earnings ratio of shares between 1920 – 1930, the acceleration phase of the second revolution, and between 1990 – 2000, the acceleration phase of the third revolution.

Figure: Two industrial revolutions: Shiller PE Ratio (price / income)

Splitting shares fuels price-earnings ratio

The increase in the price-earnings ratio is amplified because many companies decide to split their shares during the acceleration phase of their existence. A stock split is required if the market value of a share has grown too large, rendering the marketability insufficient. A split increases the value of the shares because there are more potential investors when they are cheaper. Between 1920 - 1930 and 1990 – 2000 there have been huge amount of stock splits that impacted the price-earnings ratio positively.

Table 1: Share Splits before the stock market crash of 1929

| Date | Company | Split |

| December 31, 1927 | American Can | 6 for 1 |

| December 31, 1927 | General Electric | 4 for 1 |

| December 31, 1927 | Sears, Roebuck & Company | 4 for 1 |

| December 31, 1927 | American Car & Foundry | 2 for 1 |

| December 31, 1927 | American Tobacco | 2 for 1 |

| November 5, 1928 | Atlantic Refining | 4 for 1 |

| December 13, 1928 | General Motors | 2 1/2 for 1 |

| December 13, 1928 | International Harvester | 4 for 1 |

| January 8, 1929 | American Smelting | 3 for 1 |

| January 8, 1929 | Radio Corporation of America | 5 for 1 |

| May 1, 1929 | Wright-Aeronautical | 2 for 1 |

| May 20, 1929 | Union Carbide split | 3 for 1 |

| June 25, 1929 | Woolworth split | 2 1/2 for 1 |

Table 2: Share Splits during the period 1990-2000

| Date | Company | Split |

| January 22,1990 | DuPont | 3 for 1 |

| May 14,1990 | Coca-Cola Company | 2 for 1 |

| May 22, 1990 | Westinghouse Electric stock | 2 for 1 |

| June 1, 1990 | Woolworth Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| June 11, 1990 | Boeing Company | 3 for 2 |

| May 12, 1992 | Coca-Cola Company | 2 for 1 |

| May18, 1992 | Walt Disney Co | 4 for 1 |

| May 26, 1992 | Merck & Company | 3 for 1 |

| June 15, 1992 | Proctor & Gamble | 2 for 1 |

| May 5, 1993 | Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company | 2 for 1 |

| March 15, 1994 | AlliedSignal Incorporated | 2 for 1 |

| April 11, 1994 | Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing | 2 for 1 |

| May 16, 1994 | General Electric Company | 2 for 1 |

| June 13, 1994 | Chevron Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| June 27, 1994 | McDonald’s Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| September 6, 1994 | Caterpillar Incorporated | 2 for 1 |

| February 27, 1995 | Aluminum Company of America | 2 for 1 |

| September 18, 1995 | International Paper Company | 2 for 1 |

| May 13, 1996 | Coca-Cola Company | 2 for 1 |

| December 11, 1996 | United Technologies Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| April 11, 1997 | Exxon Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| April 14, 1997 | Philip Morris Companies | 3 for 1 |

| May 12, 1997 | General Electric Company | 2 for 1 |

| May 28, 1997 | International Business Machine | 2 for 1 |

| June 9, 1997 | Boeing Company | 2 for 1 |

| June 13, 1997 | DuPont Company | 2 for 1 |

| July 14, 1997 | Caterpillar Incorporated | 2 for 1 |

| September 16, 1997 | AlliedSignal | 2 for 1 |

| September 22, 1997 | Proctor & Gamble | 2 for 1 |

| November 20, 1997 | Travelers Group Incorporated | 3 for 2 |

| July 10, 1998 | Walt Disney Company | 3 for 1 |

| February 17, 1999 | Merck & Company | 2 for 1 |

| February 26, 1999 | Alcoa Incorporated | 2 for 1 |

| March 8, 1999 | McDonald’s Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| April 16, 1999 | AT&T Corporate | 2 for 1 |

| April 20, 1999 | Wal-Mart Incorporated | 2 for 1 |

| May 18, 1999 | United Technology Corporation | 2 for 1 |

| May 27, 1999 | International Business Machine | 2 for 1 |

| June 1, 1999 | Citigroup Incorporated | 3 for 2 |

| December 31, 1999 | Home Depot | 3 for 2 |

Share Splits keep letting the Dow Jones Index explode

The Dow Jones Index was first published on May 26, 1896. The index was calculated by dividing the sum of all the shares of 12 companies by 12:

Dow12_May_26_1896 = (S1 + S2 + .......... + S12) / 12

On October 4, 1916, the Dow was expanded to 20 companies; 4 companies were removed and 12 were added.

Dow20_Oct_4_1916 = (S1 + S2 + .......... + S20) / 20

On December 31, 1927, two years before the stock market crash in October 1929, for the first time a number of companies split their shares. With each change in the composition of the Dow Jones and with each share split, the formula to calculate the Dow Jones is adjusted. This happens because the index, the outcome of the two formulas of the two baskets, must stay the same at the moment of change, because there can not be a gap in the graph. At first a weighted average was calculated for the shares that were split on December 31, 1927.

The formula looks like this: (American Can, split 6 to 1 is multiplied by 6, General Electric, split 4 to 1 is multiplied by 4, etc.)

Dow20_dec_31_1927 = (6.AC + 4.GE+ ..........+S20) / 20

On October 1st, 1928, the Dow Jones grows to 30 companies.

Calculating the index had to be simplified at this point because all the calculations were still done by hand. The weighted average for the split shares is removed and the Dow Divisor is introduced. The index is now calculated by dividing the sum of the share values by the Dow Divisor. Because the index for October 1st, 1928, cannot suddenly change, the Dow Divisor is initially set to 16.67. After all, the index graph for the two time periods (before and after the Dow Divisor was introduced) should still look like a single continuous line. The calculation is now as follows:

Dow30_oct_1_1928 = (S1 + S2+ ..........+S30) / 16.67

In the fall of 1928 and the spring of 1929 (see Table 1) 8 more stock splits occur, causing the Dow Divisor to drop to 10.77.

Dow30_jun_25_1929 = (S1 + S2+ ..........+S30) / 10.77

From October 1st, 1928 onward an increase in value of the 30 shares means the index value almost doubles. From June 25th, 1929 onward it almost triples compared to a similar increase before stock splitting was introduced. Using the old formula the sum of the 30 shares would simply be divided by 30.

Figure: Dow Jones Index before and after Black Tuesday

The extreme rise in the Dow Jones in the period 1920 - 1929 and especially between 1927 - 1929, was primarily caused because the expected value of the shares of companies that are in the acceleration phase of their existence, was increasing enormously. The value of the shares is strengthened further by stock splits and as icing on the cake this value of the shares was enlarged again in the Dow Jones Index, because behind the scenes the formula of the Dow Jones was adjusted due to stock splits.

During the acceleration phase of the third industrial revolution, 1990 - 2000, history has repeated itself. In this period there have again been many stock splits, particularly in the years 1997 and 1999.

Table 3: Summary DJIA, Dow Divisor and amount share splits between 1990-2000

| Year | DJIA | Sum 30

Shares in $

| Dow

Divisor

| Share

Splits

|

| 1990 | 2810 | 1643 | 0.586 | 5 |

| 1991 | 2610 | 1318 | 0,505 | 0 |

| 1992 | 3172 | 1782 | 0.559 | 4 |

| 1993 | 3301 | 1535 | 0.463 | 1 |

| 1994 | 3754 | 1675 | 0.447 | 6 |

| 1995 | 3834 | 1425 | 0.372 | 2 |

| 1996 | 5117 | 1770 | 0.346 | 2 |

| 1997 | 6448 | 2100 | 0.325 | 10 |

| 1998 | 7902 | 1985 | 0.251 | 1 |

| 1999 | 9181 | 2228 | 0.243 | 9 |

| 2000 | 11497 | 2317 | 0.201 | |

The formula that was used on January 1, 1990 to calculate the Dow Jones:

Dow30_jan_1_1990 = (S1 + S2+ ..........+S30) / 0.586

The formula that was used on December 31, 1999 was to calculate the Dow Jones:

Dow30_dec_31_1999 = (S1 + S2+ ..........+S30) / 0.20145268

On December 31, 1999 on an increase of the 30 stocks again nearly three times as many index points, the same value increase on January 1, 1990.

Stock market indices are mirages

What does a stock exchange index like DJIA, S&P 500 or AEX mean?

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) Index is the oldest stock index in the United States. This was a straight average of the rates of twelve shares. A select group of journalists from The Wall Street Journal decide which companies are part of the most influential index in the world market. Unlike most other indices the Dow is a price-weighted index. This means that stocks with high absolute share price have a significant impact on the movement of the index.

The S & P Index is a market capitalization weighted index. The 500 largest U.S. companies as measured by their market capitalization are included in this index, which is compiled by the credit rating agency Standard & Poor's.

The Amsterdam Exchange index (AEX) is the main Dutch stock market index. The index displays the image of the price development of the 25 most traded shares on the Amsterdam stock exchange. From a weighted average of the prices of these shares, the position of the AEX is calculated.

In many graphs the y-axis is a fixed unit, such as kg, meter, liter or euro. In the graphs showing the stock exchange values, this also seems to be the case because the unit shows a number of points. However, this is far from true! An index point is not a fixed unit in time and does not have any historical significance.

An index is calculated on the basis of a set of shares. Every index has its own formula and the formula gives the number of points of the index. Unfortunately many people attach a lot of value to these graphs which are, however, very deceptive.

- An index is calculated on the basis of a set of shares. Every index has its own formula and the formula results in the number of points of the index. However, this set of shares changes regularly. For a new period the value is based on a different set of shares. It is very strange that these different sets of shares are represented as the same unit.

After a period of 25 years the value of the original set of apples is compared to the value of a set of pears. At the moment only 6 of the original 30 companies that made up the set of shares of the Dow Jones at the start of the acceleration of the last revolution (in 1979) are still present.

- Even more disturbing is the fact that with every change in the set of shares used to calculate the number of points, the formula also changes. This is done because the index which is the result of two different sets of shares at the moment the set is changed, must be the same for both sets at that point in time. The index graphs must be continuous lines. For example, the Dow Jones is calculated by adding the shares and dividing the result by a number. Because of changes in the set of shares and the splitting of shares the divider changes continuously. At the moment the divider is 0.15 but in 1985 this number was higher than 1. An index point in two periods of time is therefore calculated in different ways:

Dow1985 = (S1 + S2 + ........+S30) / 1

Dow2009 = (S1 + S2 + ........ + S30) / 0,15

In the nineties of the last century many shares were split. To make sure the result of the calculation remained the same both the number of shares and the divider changed (which I think is wrong). An increase in share value of 1 dollar of the set of shares in 2015 results is 6.6 times more points than in 1985. The fact that in the 1990’s many shares were split is probably the cause of the exponential growth of the Dow Jones index. At the moment the Dow is at 16000 points. If we used the 1985 formula it would be at 2400 points.

- The most remarkable characteristic is of course the constantly changing set of shares. Generally speaking, the companies that are removed from the set are in a stabilization or degeneration phase. Companies in a take-off phase or acceleration phase are added to the set. This greatly increases the chance that the index will rise rather than go down. This is obvious, especially when this is done during the acceleration phase of a transition.

From 1980 onwards 7 ICT companies (3M, AT&T, Cisco, HP, IBM, Intel, Microsoft) , the engines of the latest revolution, were added to the Dow Jones and 5 financial institutions, which always play an important role in every transition.

This is actually a kind of pyramid scheme. All goes well as long as companies are added that are in their take-off phase or acceleration phase. At the end of a transition, however, there will be fewer companies in those phases. The last 18 years were 21 companies replaced in the Dow Jones, a percentage of 70%.

Overview modifications Dow Jones from 1997: 21 winners in -- 21 losers out, a figure of 70%

March 19, 2015: Apple replaced AT & T. In order to make Apple suitable for the Dow Jones, there was a share split of Apple seven for one on June 9, 2014

September 23, 2013: Hewlett-Packard Co., Bank of America Inc. and Alcoa Inc. replaced Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Nike Inc. and Visa Inc.?Alcoa has dropped from $40 in 2007 to $8.08. Hewlett- Packard Co. has dropped from $50 in 2010 to $22.36. Bank of America has dropped from $50 in 2007 to $14.48.?But Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Nike Inc. and Visa Inc. have risen 25%, 27% and 18% respectively in 2013.

September 20, 2012: UnitedHealth Group Inc. (UNH) replaces Kraft Foods Inc.?Kraft Foods Inc. was split into two companies and was therefore deemed less representative so no longer suitable for the Dow. The share value of UnitedHealth Group Inc. had risen for two years before inclusion in the Dow by 53%.

June 8, 2009: Cisco and Travelers replaced Citigroup and General Motors.? Citigroup and General Motors have received billions of dollars of U.S. government money to survive and were not representative of the Dow.

September 22, 2008: Kraft Foods Inc. replaced American International Group. American International Group was replaced after the decision of the government to take a 79.9% stake in the insurance giant. AIG was narrowly saved from destruction by an emergency loan from the Fed.

February 19, 2008: Bank of America Corp. and Chevron Corp. replaced Altria Group Inc. and Honeywell International.?Altria was split into two companies and was deemed no longer suitable for the Dow.? Honeywell was removed from the Dow because the role of industrial companies in the U.S. stock market in the recent years had declined and Honeywell had the smallest sales and profits among the participants in the Dow.

April 8, 2004: Verizon Communications Inc., American International Group Inc. and Pfizer Inc. replace AT & T Corp., Eastman Kodak Co. and International Paper.?AIG shares had increased over 387% in the previous decade and Pfizer had an increase of more than 675& behind it. Shares of AT & T and Kodak, on the other hand, had decreases of more than 40% in the past decade and were therefore removed from the Dow.

November 1, 1999: Microsoft Corporation, Intel Corporation, SBC Communications and Home Depot Incorporated replaced Chevron Corporation, Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, Union Carbide Corporation and Sears Roebuck.

March 17, 1997: Travelers Group, Hewlett-Packard Company, Johnson & Johnson and Wal-Mart Stores Incorporated replaced Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Texaco Incorporated, Bethlehem Steel Corporation and Woolworth Corporation.

Figure: Changes in the Dow Jones over the last two industrial revolutions

Figure: Exchange rates of Dow Jones during the latest two industrial revolutions. During the last few years the rate increases have accelerated enormously.

Will the share indexes go down any further?

Calculating share indexes as described above and showing indexes in historical graphs is a useful way to show which phase the industrial revolution is in.

The third industrial revolution is clearly in the saturation and degeneration phase. This phase can be recognized by the saturation of the stock market and the increasing competition. Only the strongest companies can withstand the competition or take over their competitors (like for example the take-overs by Oracle and Microsoft in the past few years). The information technology world has not seen any significant technical changes recently, despite what the American marketing machine wants us to believe.

During the pre development phase and the take-off phase of a transition many new companies spring into existence. This is a diverging process. Especially financial institutions play an important role here as these phases require a lot of money. The graphs showing the wages paid in the financial sector therefore shows the same S curve as both revolutions.

Figure: Historical excess wage in the financial sector

|

| Add caption |

Investors get euphoric when hearing about mergers and take overs. Actually, these mergers and take overs are indications of the converging processes at the end of a transition. When looked at objectively each merger or take over is a loss of economic activity. This becomes painfully clear when we have a look at the unemployment rates of some countries.

New industrial revolutions come about because of new ideas, inventions and discoveries, so new knowledge and insight. Here too we have reached a point of saturation. There will be fewer companies in the take off or acceleration phase to replace the companies in the index shares sets that have reached the stabilization or degeneration phase.

In a (threatening) recession, the central bank tries to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates. Loans are thus cheaper, allowing citizens and businesses to spend more. In the event of sharply rising unemployment and falling prices, however, this does significantly less. This is also the case as the official interest rates are lower, or even fall to essentially zero. Regardless of the interest rate (big) loans are not concluded and expensive purchases will be delayed. Further rate cuts or even an interest rate of zero may not lead to an increase in economic activity and falling demand leads to further price declines (deflation). The central bank may decide in that case to increase the money supply (quantitative easing). A larger money supply actually leads to price increases and disruption of the deflationary spiral. In the past the printing presses would be turned on but nowadays the central bank buys government bonds, mortgage bonds and other securities and finances these transactions by increasing the personal balance. There are no extra physical bank notes printed. The mechanism works by means of central banks buying bonds in the stock market or directly from banks. Banks are credited for the purchase amount in the accounts held with the central bank. In this way, banks obtain liquidity. In response to this liquidity banks can then provide new loans.

Figure: The quantitative easing policy of the Fed (US central bank) and its effect on the S&P 500

Due to the combination of interest rate policy and quantitative easing by central banks a lot of money has flowed the stock markets since 2008 and has in fact created a new, fictional bull market. This is evident in the price-earnings ratio chart (Shiller PE Ratio), which has risen again since 2008. But central banks now have no more ammunition to break the deflationary spiral. At the end of the 2nd industrial revolution in 1932 the PE Ratio dropped to 5. Currently, this ratio, partly due to the behavior of central banks, is 23. The share prices can still go down by a factor 4

Figure: Two industrial revolutions: price-earnings ratio (PE ratio Shiller)

Will history repeat itself?

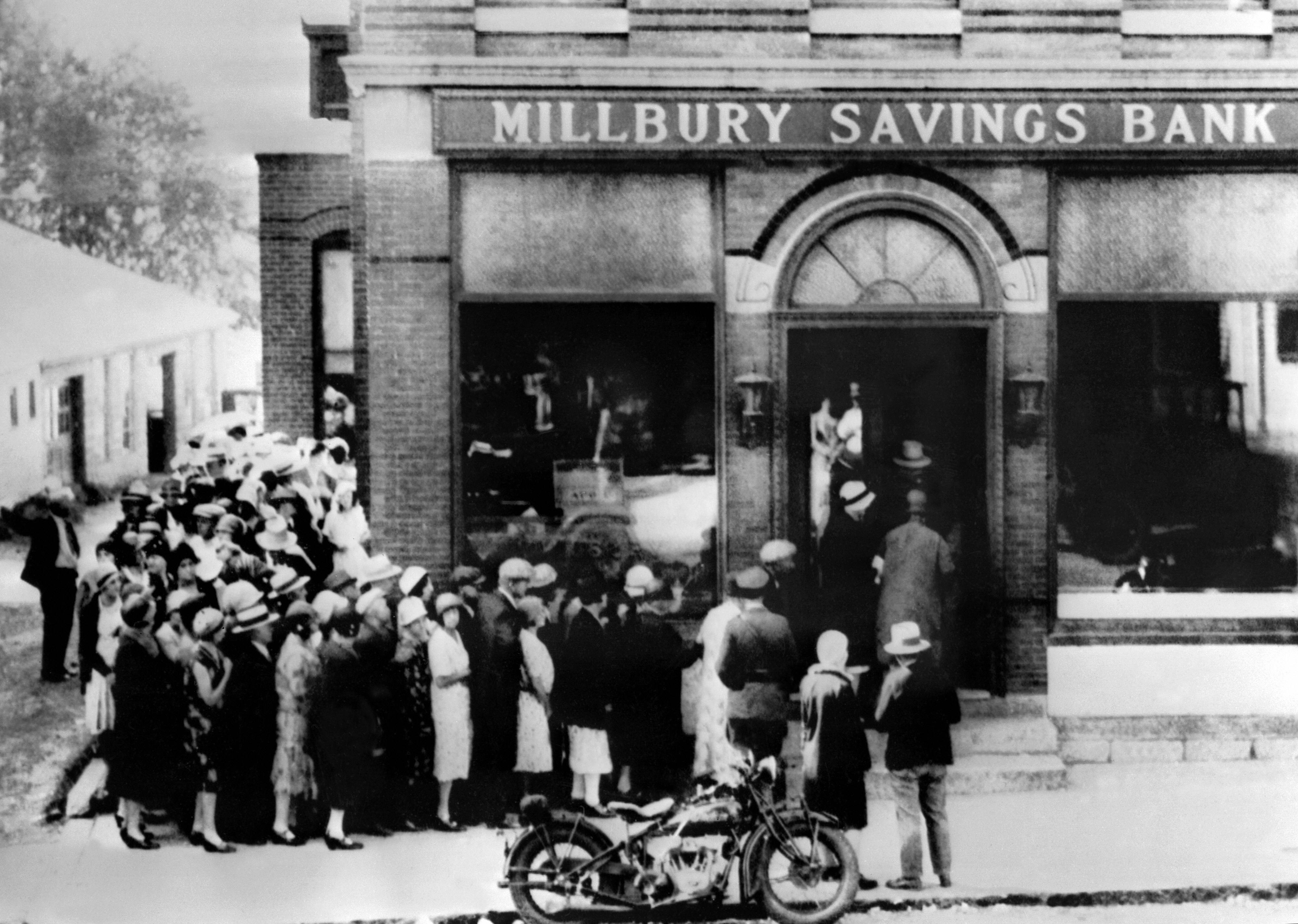

Humanity is being confronted with the same problems as those at the end of the second industrial revolution such as decreasing stock exchange rates, highly increasing unemployment, towering debts of companies and governments and bad financial positions of banks.

Figure: Two industrial revolutions and the debt of America

Transitions are initiated by inventions and discoveries, new knowledge of mankind. New knowledge influences the other four components in a society. At the moment there are few new inventions or discoveries. So the chance of a new industrial revolution is not very high. History has shown that five pillars are indispensable for a stable society.

Figure: The five pillars for a stable society: Food, Security, Health, Prosperity, Knowledge.

At the end of every transition the pillar Prosperity is threatened. We have seen this effect after every industrial revolution.

The pillar Prosperity of a society is about to fall again. History has shown that the fall of the pillar Prosperity always results in a revolution. Because of the high level of unemployment after the second industrial revolution many societies initiated a new transition, the creation of a war economy. This type of economy flourished especially in the period 1940 – 1945.

Now, societies will have to make a choice for a new transition to be started.

Without knowledge of the past there is no future.

Wim Grommen

References:

- Geschiedenis Werkplaatssite van Wolters-Noordhoff en Wikipedia

- Prof J. Rotmans, e.a. (2000), “Transities & Transitiemanagement: de casus van een emissiearme energievoorziening”

- Dow Jones Industrial Average Historical Components, S&P Dow Jones Indices McGraw Hill Financial

- Dow Jones Industrial Average Historical Divisor Changes, S&P Dow Jones Indices McGraw Hill Financial

- W. Grommen, (november 2007), “Nieuwe beurskrach, een kwestie van tijd?”, Technische en Kwantitatieve Analyse, (20 – 22)

- W. Grommen, (January 2010), “Beurskrach 1929, mysterie ontrafeld?”, Technische en Kwantitatieve Analyse, (22 – 24)

- Grommen, (March 2011), “Huidige crisis, een wetmatigheid?”, Hermes, 49, (52 – 58)

- Grommen, (January 2013), paper “The present crisis, a pattern” gepresenteerd op International Symposium The Economic Crisis: Time For A Paradigm Shift

- W. Grommen, (November 2014), “The Dow Jones Industrial Average , A Fata Morgana”, TRADERS’Magazine, (14 – 18)

- Grommen, (April 2015), “Stock Splitting And The Market Crash 1929”, ValueWalk

- Grommen (August 2015), "Stock Market Boom and Crash, the Cause and Effect of Extreme Market Movements” , TRADERS’ Magazine, (28 – 3